1. Waters of Lake Minnatonka

The box office dip initiated by Internet insurgents NETFLIX, AMAZON, and HULU finds an easy visual metaphor in the watermark drop noticeable by any hike-trekking Angelino over the past two years. Of soothing desert water, lapping weekly with a shallower depth, in the Elysian reservoir over north L.A. Its scorched, showing basin and dwindling volume somehow an apt signifier for the bygone era of abundant 20th Century movie theatre attendance, these days in various stages of becoming ‘all dried up.’

Film history itself dawned with water on the brain. August and Louis Lumiere used it to sell their cinematographe, and humankind’s first-ever silver screen sight gag in The Waterer Watered.

Documentarian and avant-garde pioneer Ralph Steiner too made his first film, an experimental one, about the Gaussian façade of the celluloid image and its formal relationship to liquid play. This in 1929 tone poem, H20.

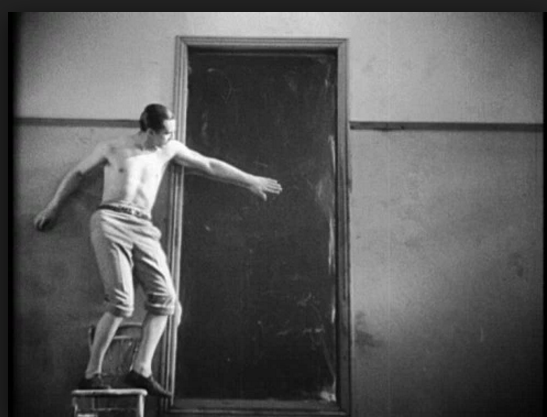

Jean Cocteau’s “artist”, also, enters this side of the looking glass, establishing queer cinema with it in 1930 jumpstart, Blood of a Poet. And therein, experiences film’s voyeurism at its other end. The character’s transport, essentially “into film”, is done through an effect with water.

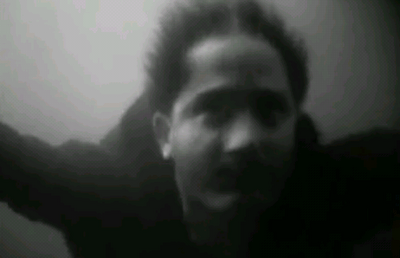

And surrealist social realist Jean Vigo, without whom the subsequent French New Wave and Italian Neo-Realism both would’ve maybe never happened (the formal instincts of the first, the social humanism of the second) made an even bigger splash a year before his 1934 death in his masterpiece L’Atalante.

Inventing a gorgeous metaphor, sworn by OG pixie dream-girl Dita Parlo, Vigo’s character is able to open her eyes in a bucket and see her one true love by looking through water.

When narrow-minded grump husband and canal barge captain Jean Daste loses her to some city fella and the wiles of adventure and easy living to which Daste dislikes, he topples overboard and realizes she’s right. Dita’s happy image swims before him and us in an underwater fantasy come true, breathtaking and buoyant with glee. Convinces him to get her back. It’s like he’s watching her in a theatre himself, her face a giant movie star flicker he can just barely reach out and touch.

Cinematic visual pleasure and Freudian dream-logic combine here to show love in the tangible—and do so with one of film’s oldest accomplices: water.

Dunking our heads in the bucket of film history, we see film’s symbolic and formal love of liquid again and again in its milestone moments—from Maya Deren in her 1942 near-invention of independent and art cinema, Meshes of the Afternoon to Stan Brahkage’s affirmation of lyrical mythopoeia, Window Water Baby Moving, all the way to Terrance Mallick’s unintended 2011 partial-massacre of it, Tree of Life (aside from the bloated oceanic hand-touching, a film that is still actually sorta in places good).

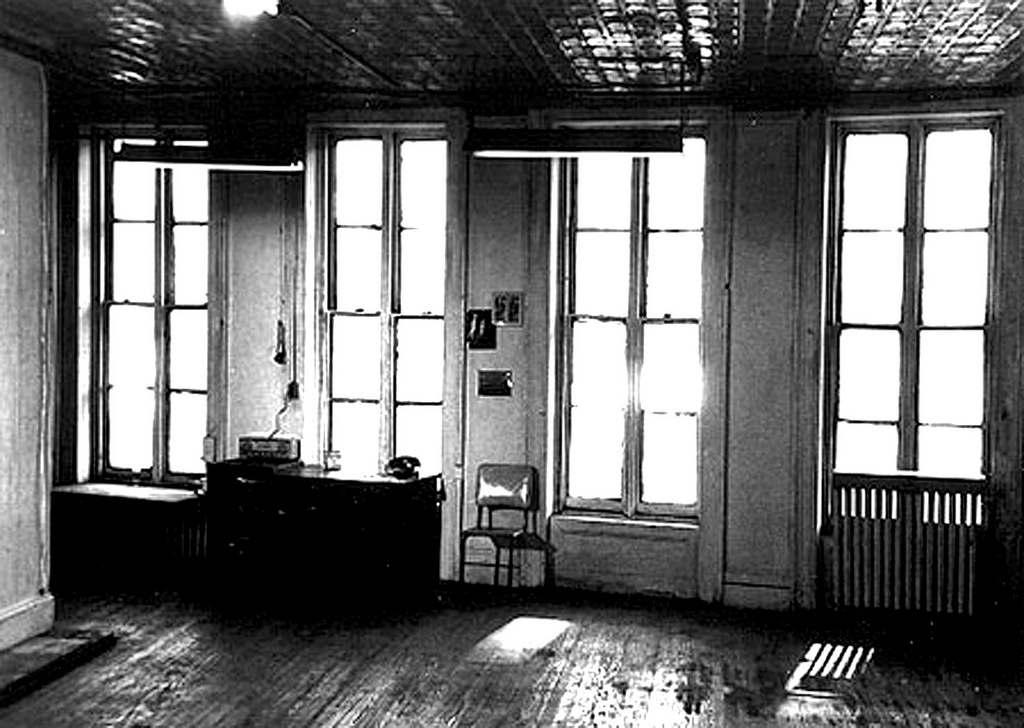

Even Michael Snow's 1967 film Wavelength—a landmark of structuralist cinema and an experimental film-hater's wet dream—lands its 45 minute single camera move across a studio apartment on a linguistic play-on-words and a transcendence of the two dimensional image, focusing eventually on a wall-hung picture of the sea.

Amidst rocky waters in the film industry, let's submerge ourselves, then. Purify ourselves in Purple Rain’s metaphorical Lake Minnetonka (as a Minnesotan spiritual tundra will prove later restorative…) Recapture what we love about moving image, our eyes open beneath the surf. See whether the twilight of the Big Screen means with it the drowning of the 20th Century film language we praise so: cinema.

A few glaring obstructions to watch out for as we dive: Story content these days, especially current reserves streaming by the online tides of change, is crafted for an oft-attention divided audience, with a penchant for nostalgia, and with a serializing mandate in the minds of producers. Sometimes this means prolonged narratives for cash-cow purposes alone (this is nothing new—ever since MGM adapted their ‘Art For Art’s Sake’ slogan the hypocrisy of Development Executive output for reasons of monetary gain over narrative urgency is rote.)

Other times it means stories so chock-full with run-of-the-mill life-and-death drama so as to numb any viewer to all the crazy-impactful (and subtle!) things that make people want to share human stories to begin with (paging long-running seasons of LOST, Sopranos, Game Of Thrones, hell-bent on killing, mating, sometimes even reviving characters willy-nilly just to keep audiences arbitrarily glued to the tube).

And worse, all of it in a visual language meant for watching between newsfeed swipes and up-to-the-minute texts on a 5’ phone screen (though that size is constantly changing).

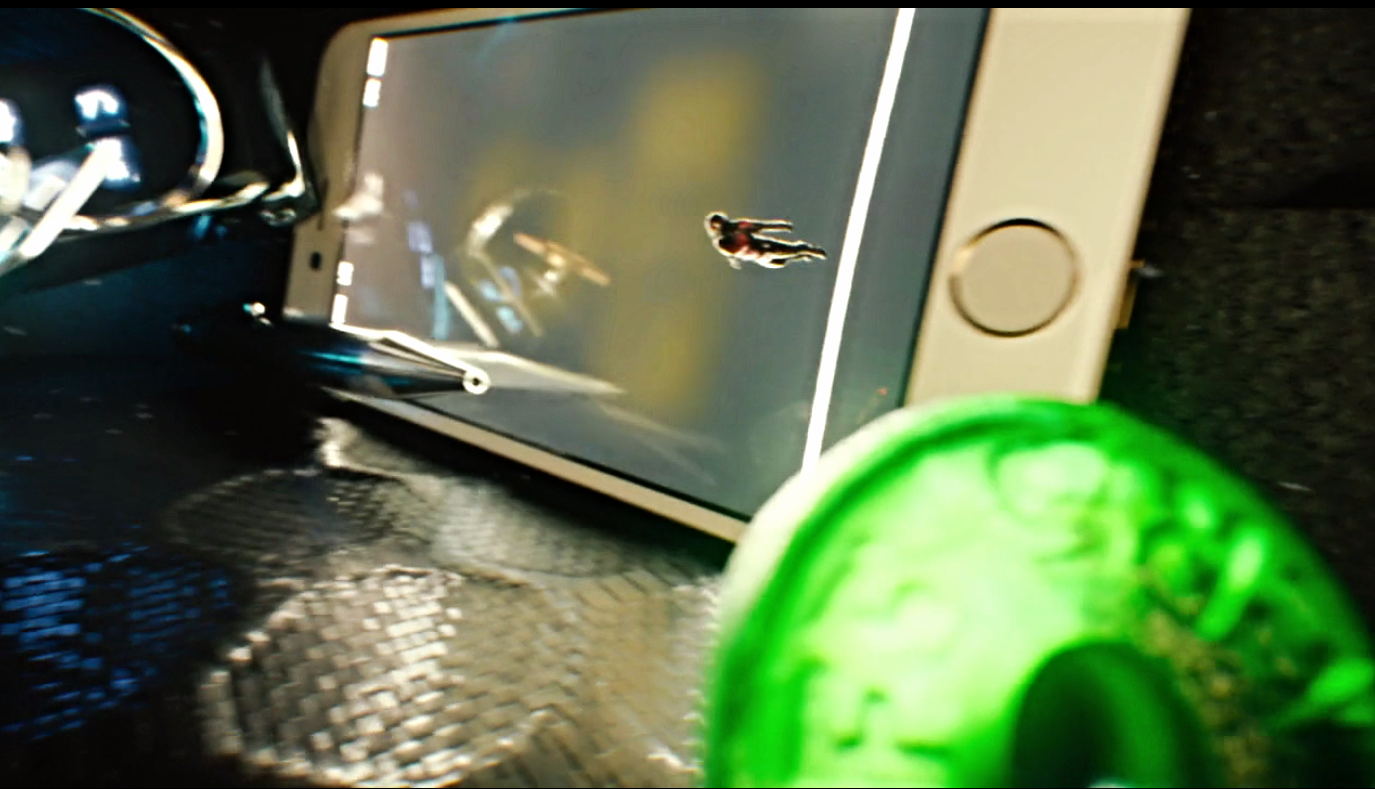

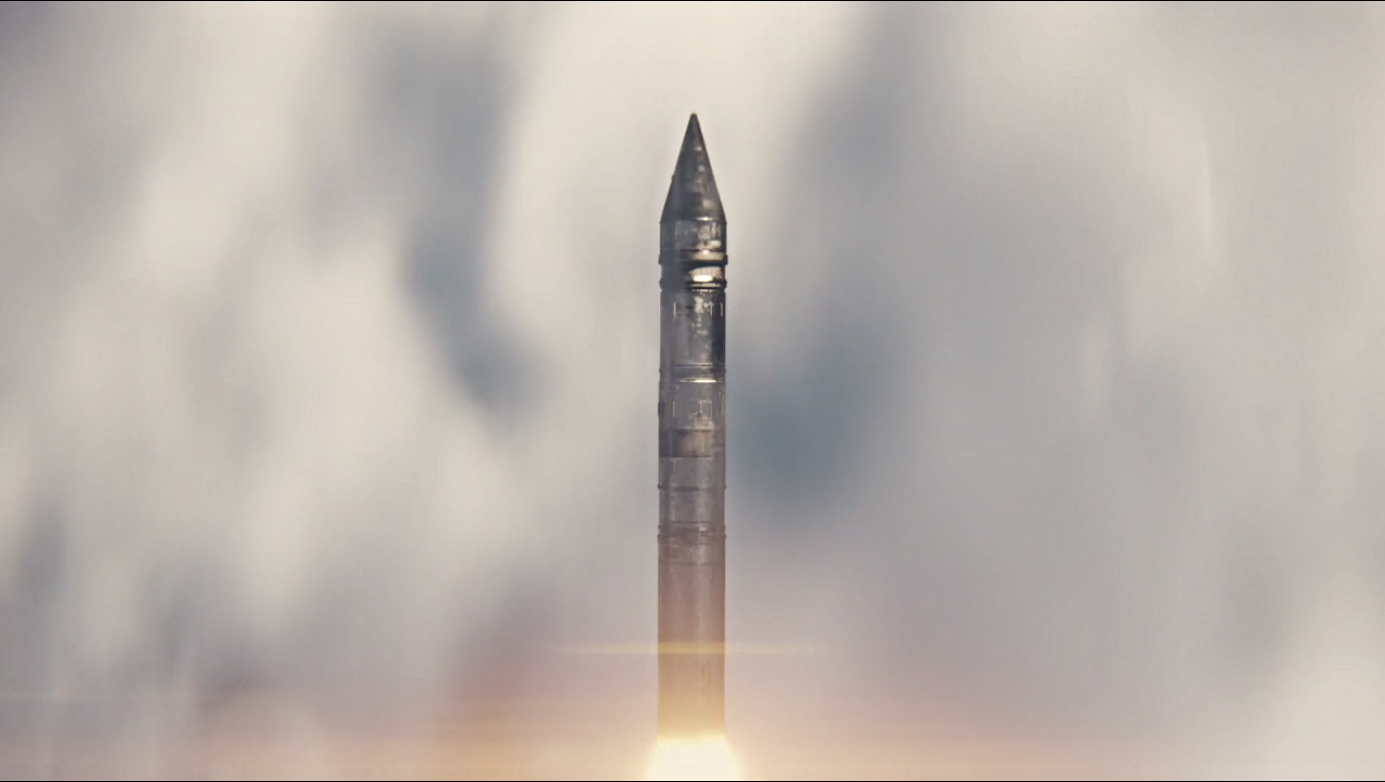

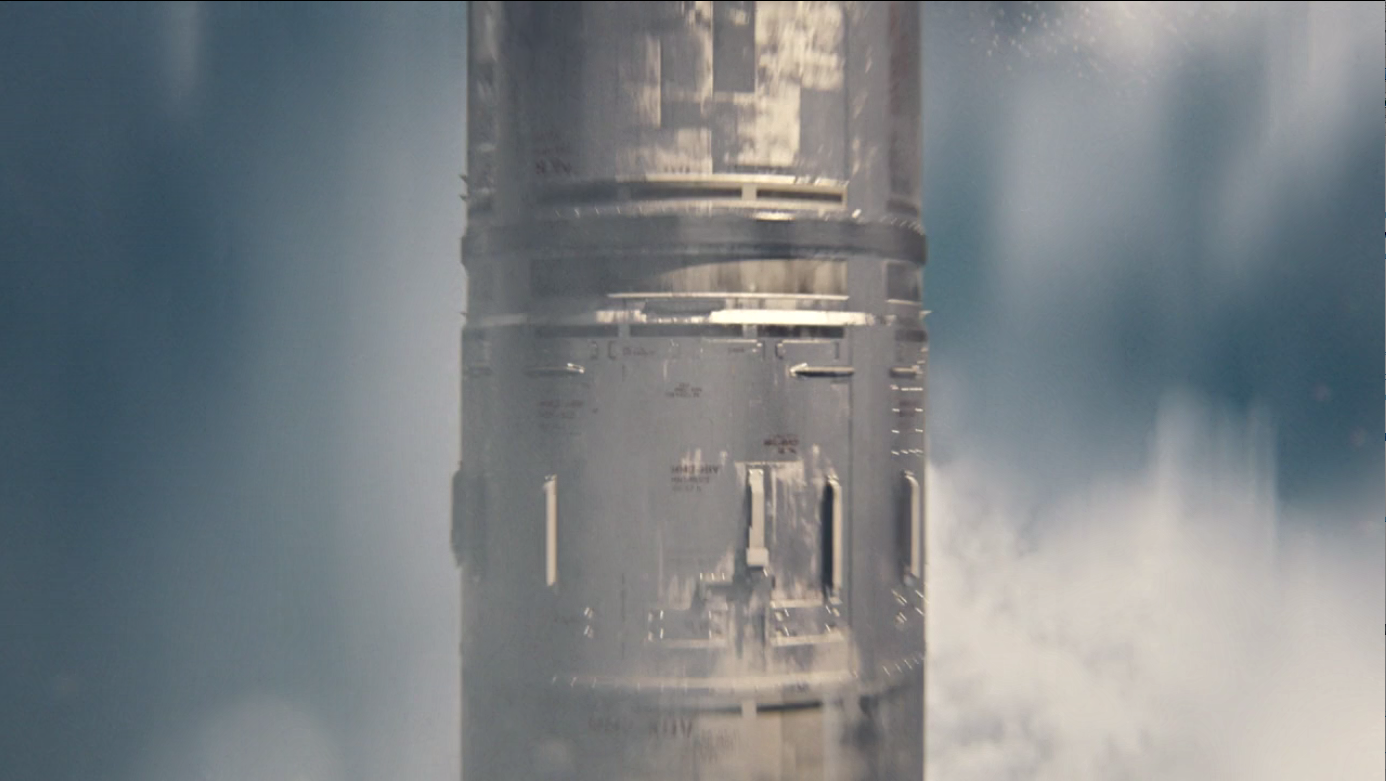

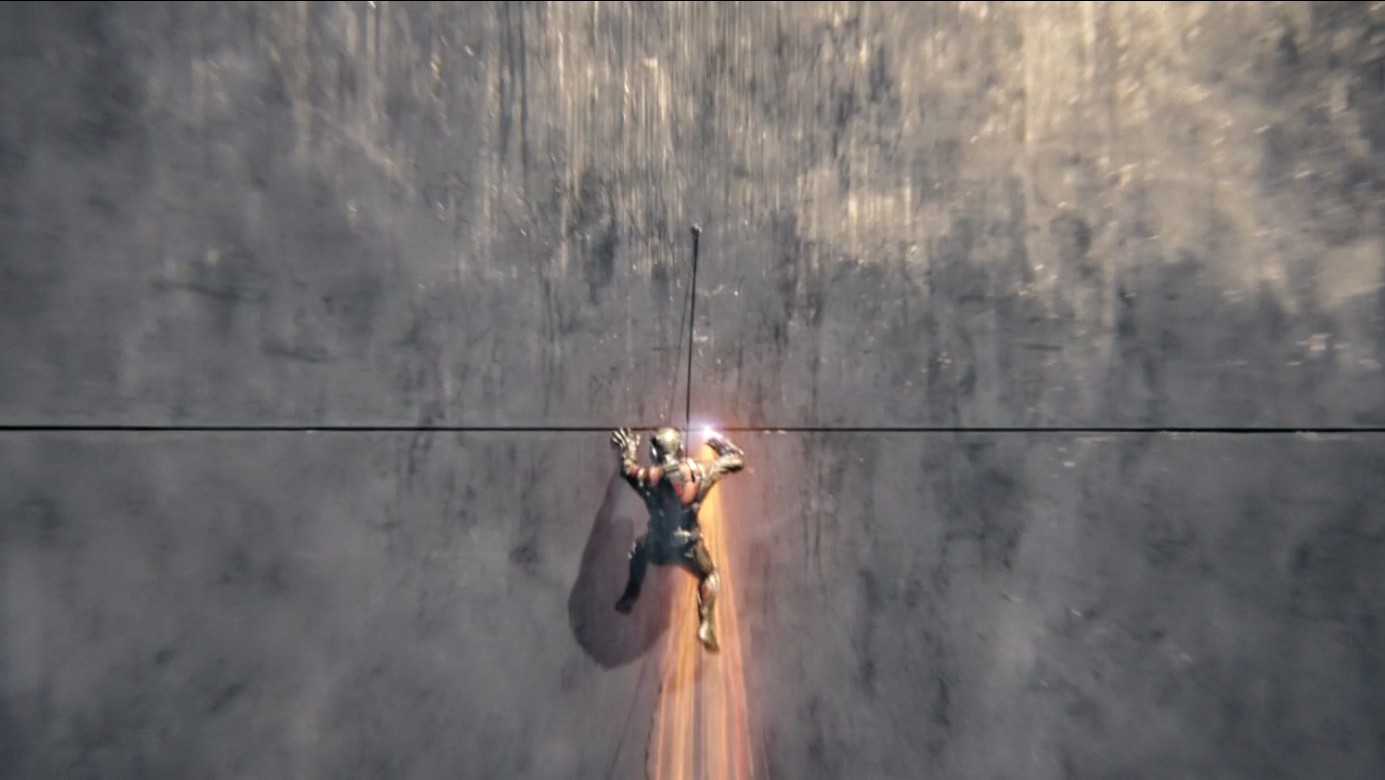

How we watch moving images is an area where size does potentially matter, and film form and function must meet for us to pick up the film language that's being put down. Take 2016's superhero lark Ant-Man (above), a project contracted to British genre auteur Edgar Wright for the quite overstated 'Marvel Cinematic Universe' (MCU), and completed by Hollywood yes-man Peyton Reed. The film, whose set-up is intrinsically focused on size and scale, un-ironically epitomizes the over-abundant close-up shooting style of the small screen mentality—and this far outside of the Phase IV-reverent macro-photographic insect action scenes which become its better moments.

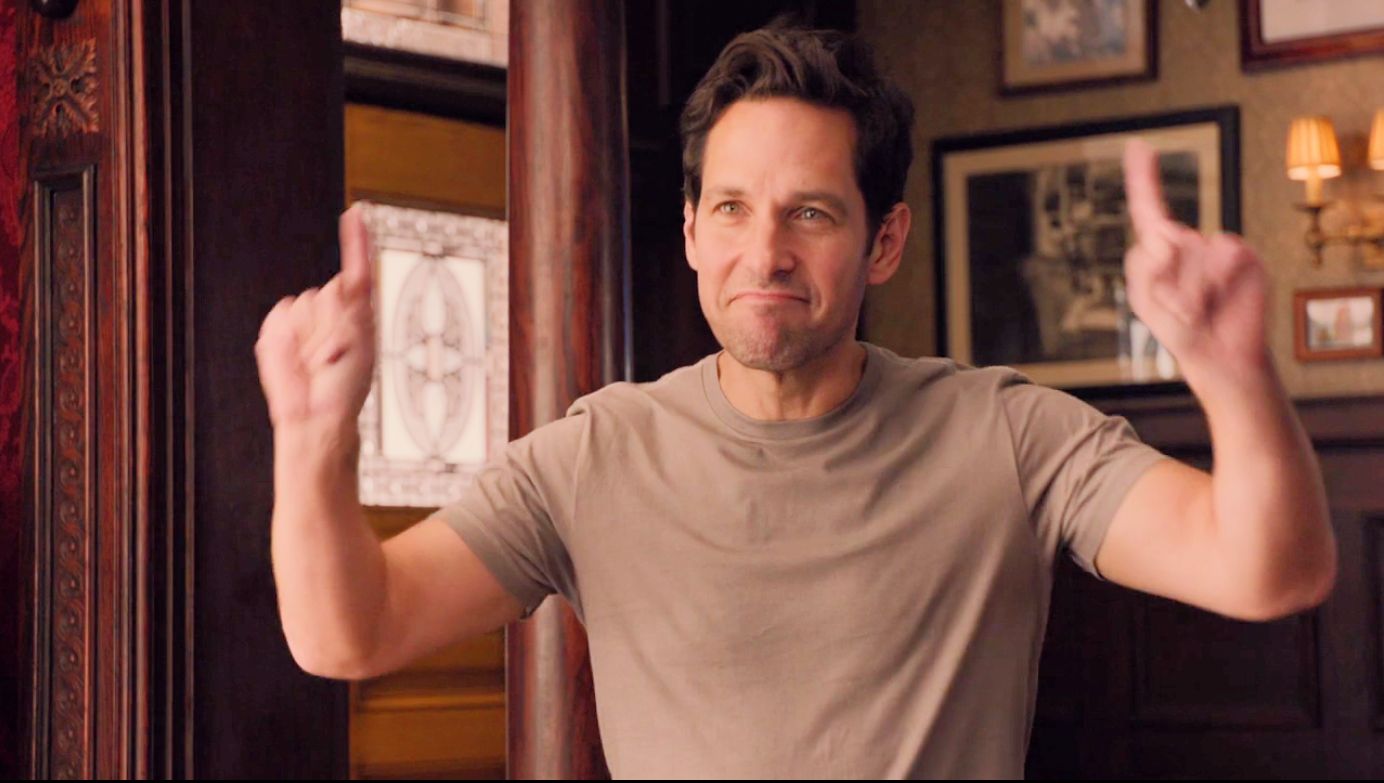

Take the below scene (this a simple dramatic one between humans): a father-daughter confession intercut with a life-altering flashback is supposed to be interrupted by a socially daft Paul Rudd at its climax. Rudd enters the scene with Evangeline Lily at the opening, the intention being to have you forget he's there until he interrupts a touching family moment with a blundering aside. But the entire scene is shot mostly with close-ups. The number of times the editor has to cut away to line-less Rudd so we're not confused to see him in a medium shot later obliterates the joke about him being still in the room when it hits—a problem that could have been solved, and funnier, with a cut out to a simple establishing wide as a reveal with all three characters in frame for the climax, ditching Rudd's useless other cut-away moments.

The most resinating take-away is how the scene as-is works disproportionately more on the small screen than the big one where I first saw it. It also begs the question: was it shot this way understanding that, of all its Marvel properties, one so fraught with fan-boy disillusionment as this, considering Wright's very public departure from the project, would likely feel that impact in the box office? Would likely go down swinging in a theatrical underperformance (which it did), the majority of its life existing on streaming rentals meant for Marvel mega-fans needy to for MCU installments between their bigger releases? Meaning a scene full of close-ups resonating far more in that context than in traditional theatrical viewing?

Because if films are now being deliberately shot to perform on small screens the way TV has for decades, it could mean the life-force of visual language—what Andre Bazin called ‘cinema’—potentially evaporating into thin air. (To be fair, entertainment fails when it fails cinema. The problem with Ant-Man is it actually doesn't realize Bazin's chapter on Virtues and Limitations of Montage exits, size of screen be damned.)

And what is this sacred water, cinema—does it differ from the leveed delta of mere entertainment sludged into the homes and minds of millions? (Steven Soderbergh—perhaps one of the most formally reserved of that small camp of Hollywood auteurs born from the indie fray, would agree yes it is.)

Ultimately, is there a way to think of both 'cinema' and 'entertainment' as existing all in one tide pool—together contained in some representative territory, governed by human interest and spiritual need? One where something about the demands of our humanity can be explored, and the medium in full with it?

I return to that craggy-faced basin, easy to spot on a Hollywood hike, drained by desert heat. Its resources holding steady for the daily wanderer. Ready to deliver, shimmering, through the tap.